How about a SUNDAY SWIM in the canal (in the future)?

EN

Introduction

There is no official outdoor swimming location in Brussels today. Nevertheless, people still swim in the canal — driven by necessity and the lack of alternatives. This situation inadvertently makes the Port of Brussels the only authority effectively managing an outdoor swimming spot in the city. Could swimming in the canal in Brussels become a valid, official option for outdoor swimming?

▶︎ In a previous article, we explored various options for enabling swimming in the canal. This time, we focus on the most direct and simple approach: swimming in the existing, untreated water of the Brussels canal itself. Understandably, this idea raises questions — and rightly so. But we are convinced that, with the right measures in place, it is possible to organise canal swimming in a way that is responsible, safe, and comfortable for all.

1935 at the Porte de Ninove: canal swimmers 90 years ago …

… and today in 2025 at the ponton of the CRBK in Anderlecht.

Swimming directly in urban waters is already common in several cities: consider Copenhagen, Basel, more recently Paris and Duisburg. Other cities like London or Berlin are also exploring such possibilities. These cities all have very different characteristics and water bodies, yet they share one ambition: to become swimmable cities by opening ports, canals and rivers to swimmers.

The advantages of swimming directly in the canal in Brussels are obvious: it is the largest water body in the city, deep enough for swimming, and could be made accessible with simple, inexpensive infrastructure like pontoons with ladders. Yet while the Port of Brussels — the responsible public authority managing the canal — is open to floating pools in the canal and swimming areas separated from the canal water, it remains firmly opposed to swimming directly in the canal itself, even for occasional events. There are three reasons for this: firstly, legislation that simply prohibits swimming in the canal; secondly, their consistent communication line that swimming is dangerous and therefore forbidden; and thirdly, what they see as clear dangers, listed in a risk analysis that was shared with us as part of a penalty following the Big Jump event in 2018.

This article aims to respond to that list of risks, re-evaluating them and proposing methods and techniques to address them, so that swimming in the canal can become possible in a safe and responsible way. But before looking at the specific challenges of managing the risks of outdoor swimming in the canal, we need to consider how risks are perceived, and how responsibility can be shared to deal with them.

Dealing with risks in general

Risks must be judged realistically. While they can be managed as effectively as possible, they can never be completely eliminated.

To illustrate this, consider the risk of swimming — whether in the canal or elsewhere — compared to the risk of traffic. Accidents happen, sometimes fatal ones, despite clear rules, solid infrastructure and public education on how to behave in traffic. Yet nobody would propose banning pedestrians from walking on the streets because cars exist.

Managing risk requires a twofold strategy. It is the responsibility of each individual to judge their own capabilities and the circumstances around them. To judge those circumstances, the relevant factors must either be directly visible, or proper information must be provided so that people can make an informed judgment. Authorities have the responsibility to create infrastructure that can be assessed visually (e.g., platforms, ladders, stairs) and to communicate clearly about parameters that individuals cannot judge themselves (e.g., water quality, currents, temperature, depth). Authorities must also ensure safety by regularly checking and cleaning the bottom of the swimming area to remove debris or trash. Conversely, individuals have the linked responsibility to follow common rules — such as not throwing trash into the water.

It is always possible that third parties create danger, despite everyone else acting carefully. For instance, a driver might miss a red light (deliberately or due to technical failure) and drive through a pedestrian crossing, even though pedestrians trusted the green light. The same could happen on the water: swimmers might encounter boats that fail to follow rules. Still, society does not see crossing the street with a green light as especially risky; pedestrian crossings and traffic lights exist everywhere. Even unmarked crossings exist, and although accidents do happen, they are rare. On the water, there are far fewer boats in the canal than vehicles on a road. The risk of swimmers and boats interfering should therefore be approached similarly — comparable to managing risk in traffic.

A comprehension of how we see a share of responsibilities for safe outdoor swimming in Brussels

Responsibilities of authorities:

Provide appropriate infrastructure

Carry out maintenance to keep the place safe and clean

Share clear information about invisible risks

Educate the public on risks and basic rules

Support swimming lessons

Responsibilities of individuals:

Learn about risks and basic rules

Seek information on invisible risks

Treat infrastructure with respect

Understand and, if needed, improve personal swimming capabilities

Look out for others (children, friends, strangers)

Risks of swimming in natural water

Swimming always carries risks, like any other activity. In traffic, danger can be judged visually; in the case of air pollution, it can sometimes be smelled or seen (but not always). Natural water, however, is opaque, unlike a swimming pool, and cannot be fully assessed by the human senses. While water temperature can be felt and judged personally, water quality — such as bacteriological contamination — cannot be perceived directly. Similarly, the depth or objects at the bottom usually remain invisible.

Therefore, someone must observe and evaluate these invisible risks, and communicate clear and comprehensible information about them. This requires a relationship of trust: individuals must trust that authorities provide accurate and up-to-date information, and authorities must trust that individuals read, understand and use that information responsibly.

Risks of swimming in the canal of Brussels

The canal in Brussels is an artificial water body, used today mainly for shipping. It is also the city’s largest body of water. It serves as a habitat for fish and other aquatic life, acts as a rainwater buffer during storms (which brings its own problems, as discussed below), and provides open space and long views in Brussels’ dense urban landscape. It is already used for recreation along its quays, parks and cycle paths, and on the water itself, through rowing and kayak clubs, sailing lessons and boat cruises. But this is where it stops. Could the canal also become a swimming spot? In reality, it already is — unofficially. To answer that, we must look more closely at the canal itself and its specific risks.

A differentiated look at the canal

The canal is unlike a river, which is typically a continuous, uniform water body. Instead, the Brussels canal consists of very long, narrow stretches of water connected only by locks, which means there is limited water exchange under normal conditions. In Brussels, the canal can be divided into three parts:

The southern part: from the Brussels Region border at Ruisbroek to the Anderlecht lock

The central part: between the Anderlecht and Molenbeek locks

The northern part: from the Molenbeek lock to the regional border with Vilvoorde

The three parts of the canal in Brussels

Sewage overflows into the Senne river, the canal (red-white dots) and confluences of streams into the canal (blue-white dots).

Most of the time, water only flows when boats pass from a higher to a lower section. Although there is a constant slow flow from south to north, there is hardly any current under normal conditions. This can change drastically during rainstorms when sewage overflows into the canal cause significant currents and immediately worsen water quality. This is discussed in more detail below. Importantly, these overflows are not evenly distributed: several exist in the central and northern canal, but there are none in the southern part within Brussels, and only a few minor ones further south on Flemish territory. As a result, water quality on average is significantly better in the southern part than elsewhere.

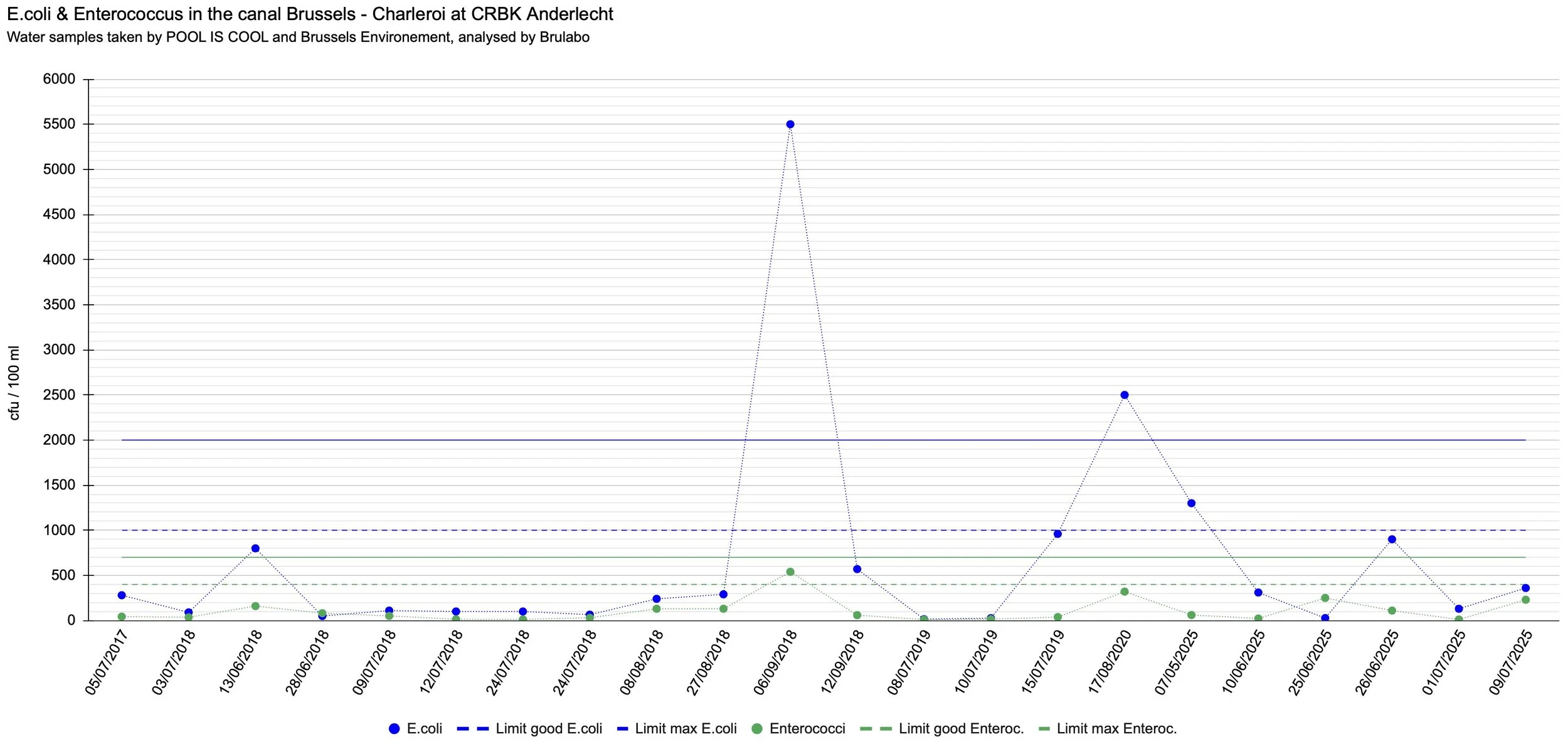

All countries in Europe have to follow a ▶︎ European directive for the assessment of bathing water. This directive defines the rules on how to assign a quality label to a swimming place: excellent, good or sufficient water quality. However, this assessment requires regular measurements over the course of 4 years, with a certain percentage of measurements staying under specific limits. It does not define limits for a single measurement. To evaluate the water quality at a certain moment, local authorities have the freedom to define the limits themselves. However, since there is no swimming water in Brussels, the Brussels government never defined these limits. Therefore we applied ▶︎ the regulations of our closest neighbours: Flanders.

Based on the tests we conducted at irregular moments in the past 8 years, we can say that in more than 90% of analyses, water in the southern canal is fit for swimming according to the Flemish standards for inland freshwater swimming areas. Contrarily, in the few tests conducted in the central or northern parts, these standards were not met, so swimming there cannot be recommended based on current data.

E.coli & Enterococcus in the canal Brussels - Charleroi at CRBK Anderlecht

Another important factor is the canal’s morphology throughout Brussels. Sometimes it is as narrow as 20 metres, just wide enough for two ships to pass; elsewhere, it widens into harbour basins up to around 120 metres. Along its length there are mostly quay walls up to 5 metres high, but in some places there are sloped green banks. Some stretches are directly accessible, while others border private, mostly commercial, sites. The canal’s depth also increases from south to north, from about 3.5 metres in the southern and central parts up to about 6.5 metres in the north.

Thirdly, shipping traffic varies across the canal. Large ships have 24/7 access to the canal from the north as far as the Vergote basin. It is also in the northern part that most commercial facilities supplied by ship are located. Further south, navigation depends on the opening hours of the locks, which means that shipping traffic in the south of Brussels is limited on average. In addition, commercial inland shipping is prohibited throughout Belgium on Sundays. This means that no large barges travel through Brussels on Sundays, and only smaller pleasure boats might pass.

These differences in water quality, morphology and shipping traffic show why it is essential to distinguish between different parts of the canal — and even specific locations — when discussing the possibility of swimming: each area has different challenges and opportunities.

Focus on the southern part of the canal

Considering all the factors mentioned above, we believe that the southern part of the canal is particularly suitable for swimming in the future. In the central and northern sections, floating pools or other swimming facilities that use water separated from the canal itself would be more appropriate for now. But in the south, we see an immediate opportunity for swimming directly in the canal.

One particularly interesting area lies along the western bank, between the rowing club and the kayak club. Between the kayak club’s pontoon and an existing slipway there is enough space for a 50-metre-long swimming zone. Simple infrastructure, like lifeguard stations and changing cabins, could be placed on floating pontoons. In the water itself, a swimming zone of about 50 by 8 metres could be installed without obstructing the passage of ships, small recreational boats or water sports users. This could be set up permanently, or at first temporarily during the summer as a test. We believe swimming there could even be possible at times when large ships are passing. However, starting with a Sunday Swim programme could be a good way to test swimming in the canal, since on Sundays no large commercial ships travel through Brussels.

All it takes is a very simple floating infrastructure: a ponton, two ramps to access it, and a light frame with a line of buoys to define a 50 x 8 m large swimming zone.

Are you in for a Sunday Swim?

How to deal with the risks identified by the Port of Brussels

The greatest challenge in making this vision reality remains convincing the Port of Brussels, the authority managing the entire canal. Permission from the Port would be essential for swimming to be allowed. Interestingly, swimming in this section of the canal is not fully prohibited by law. The relevant ▶︎ regional police regulations for the port (in effect since 2010) do not mention swimming at all. The other relevant legal framework is the ▶︎ “General Police Regulations for Navigation on Inland Waterways.” Article 6.37 of this regulation states that swimming is allowed if the swimming zone is properly marked with specific water traffic signs. This means that in principle, swimming is legally possible.

Nevertheless, the Port of Brussels produced a risk analysis listing the following risks of swimming in the canal:

Risk analysis for swimming in the canal in general by the Port of Brussels, 2018

Accident risks – risk of injuries

Cuts or scratches from contact with metal objects, glass or other items not detected on the bottom or banks

Thorny plants on the banks

Bites from wild animals frequenting riverbanks and canal edges (e.g., rats)

Injury when jumping into the water due to a blunt object that was not visible on the bottom

Collision with a floating object just under the surface, unseen because of the opaque water (e.g., wooden beam)

Collision with a vessel ignoring the prohibition on navigating through the swimming area

Accident risks – risk of drowning

Hydrocution (cold shock): swimmer sinks unseen because of opaque water

Swimmer becomes unconscious after collision and sinks unseen

Inexperienced swimmer sinks unseen

Swimmer in distress sinks unseen

Swimmer swept away by current when lock gate opens, falling into the lock, and cannot be rescued

Panic after an incident; location lacks enough exits to allow many swimmers to leave the water quickly

Passage of a boat creates suction that could pull swimmers out of the swimming zone, leading to dangerous collisions

Health risks

Sanitary condition of the water changes between time of analysis and time of swimming

A harmful germ not detected during testing

Bites or stings from animals (e.g., rats) or insects

Presence of heavy metals or other pollutants in the water

It is important to point out that these risks are not unique to the Brussels canal; they also apply to virtually every natural swimming location. In fact, swimming does take place at many other sites with similar conditions — both in Belgium (for instance, seasonally in Keerdok Mechelen, Bonapartedok Antwerp and the canals of Bruges, or during events in the port of Ghent and at ▶︎ the various locations where the BIG JUMP can take place in Belgium) and abroad.

Accident risks – risk of injuries

Cuts, scratches or fractures caused by contact with a metal object, glass or other debris not detected on the bottom or on the bank

This is indeed a real risk, and there have been reports of people actually touching or injuring themselves on submerged objects. In the past, bicycles have been pulled out of the canal near the pontoon of CRBK. To make swimming safer, the bottom of the canal in the area where people might jump in and dive should be cleaned by divers to remove debris. We collaborated with a local diving company to do exactly this during the ▶︎ Expedition Swim in 2019. In other places, such as in Flanders, this work is often done by divers from the fire brigade. Cleaning should be performed before the main swimming season in summer and can be repeated mid-season if needed. Additionally, the organisation managing the swimming zone can regularly carry out floor inspections by dragging nets over the bottom to detect any new debris. If debris is found, divers can then be called to remove it. Signage at the pontoon should inform people about the water depth, and swimming can be discouraged if the water is too shallow. With these measures, the risk of injury can be greatly reduced.

Thorny plants on the banks

Plants along the banks should simply be trimmed wherever swimmers might come into contact with them. This task falls to the organisation responsible for maintaining the swimming zone.

Bites from wild animals frequenting riverbanks and canal edges (e.g., rats)

In general, animals — including rats — tend to be more afraid of humans than the other way around. Bites leading to injuries or infections do happen, but are extremely rare. To reduce this risk further, pontoons could be placed slightly away (about a metre) from the shore. Regular cleaning and prompt removal of any rubbish that could attract rats will help make the swimming area less appealing to them, thereby reducing the chance of encounters.

Injury while jumping into the water because of unseen blunt objects

The same preventative measures mentioned earlier — regular diving inspections, cleaning, and floor net sweeps — apply here as well.

Collision with a floating object just beneath the surface, unseen due to the opaque water

A practical solution is to delimit the swimming zone with a line of buoys, to which a net is attached reaching down to the bottom. This net will prevent objects from floating into the swimming area. It is also worth noting that in the southern part of the canal there tends to be less floating debris than in other sections.

Collision with a vessel that ignores the prohibition on navigating through the swimming area

This risk could result from human error or technical problems. The most important measure is clear communication to all boat and ship operators about the location of the swimming zone. This can be achieved by placing the required traffic signs well in advance of the zone, and marking the swimming area itself clearly with highly visible buoys and floating lines. For permanent swimming zones, additional protective structures such as deflecting poles or beams can also be installed in the canal, though this is a more costly option.

Besides measures aimed at boats, swimmers themselves can also be alerted to approaching vessels. This can be done by lifeguards or staff responsible for managing the swimming area who keep watch visually, or by installing camera systems monitoring the canal in both directions. These cameras can be linked to image recognition software that automatically detects approaching boats and triggers an audible or visual warning in the swimming zone, allowing swimmers to leave the water safely in time.

If swimming is permitted during times when large commercial vessels might pass, swimmers could also be warned in real time using data from the ships’ ▶︎ Automatic Identification System (AIS). This system broadcasts each ship’s position, course, and speed at least every 30 seconds. With enough AIS receivers installed along the canal, it becomes possible to predict a ship’s trajectory very accurately. This data is already visualised on websites like ▶︎ MarineTraffic and ▶︎ VesselFinder. AIS data could be integrated into a local system to trigger on-site warnings or alerts in a dedicated swimming app.

Accident risks – risk of drowning

The points raised about drowning focus not so much on the drowning risk itself, but on the concern that a drowning person might not be visible to lifeguards or other swimmers because of the canal’s opaque water. In the southern part of the canal, the water clarity — or visible depth — is about 60 cm. This level of opacity is very common for natural swimming water in central Europe.

Countless swimming areas — including many in Belgium — have similarly opaque water, yet people swim safely in them every year. The fact that these places are authorised and properly equipped shows that the risk is not unacceptable, but instead manageable.

It’s also important to note that lifeguards typically spot swimmers in difficulty not by seeing them underwater, but by observing their behaviour at the surface. Most rescues start because someone notices signs of distress above the water. Full water transparency can help, but it is not strictly essential if surveillance is done correctly.

Hydrocution: swimmer sinks unseen because the water is opaque

Hydrocution, also known as cold water shock, can occur when someone overheated from sun exposure or exercise suddenly enters cold water, leading to rapid temperature change. This can trigger dangerous responses like fainting or even cardiac arrest, which could result in drowning.

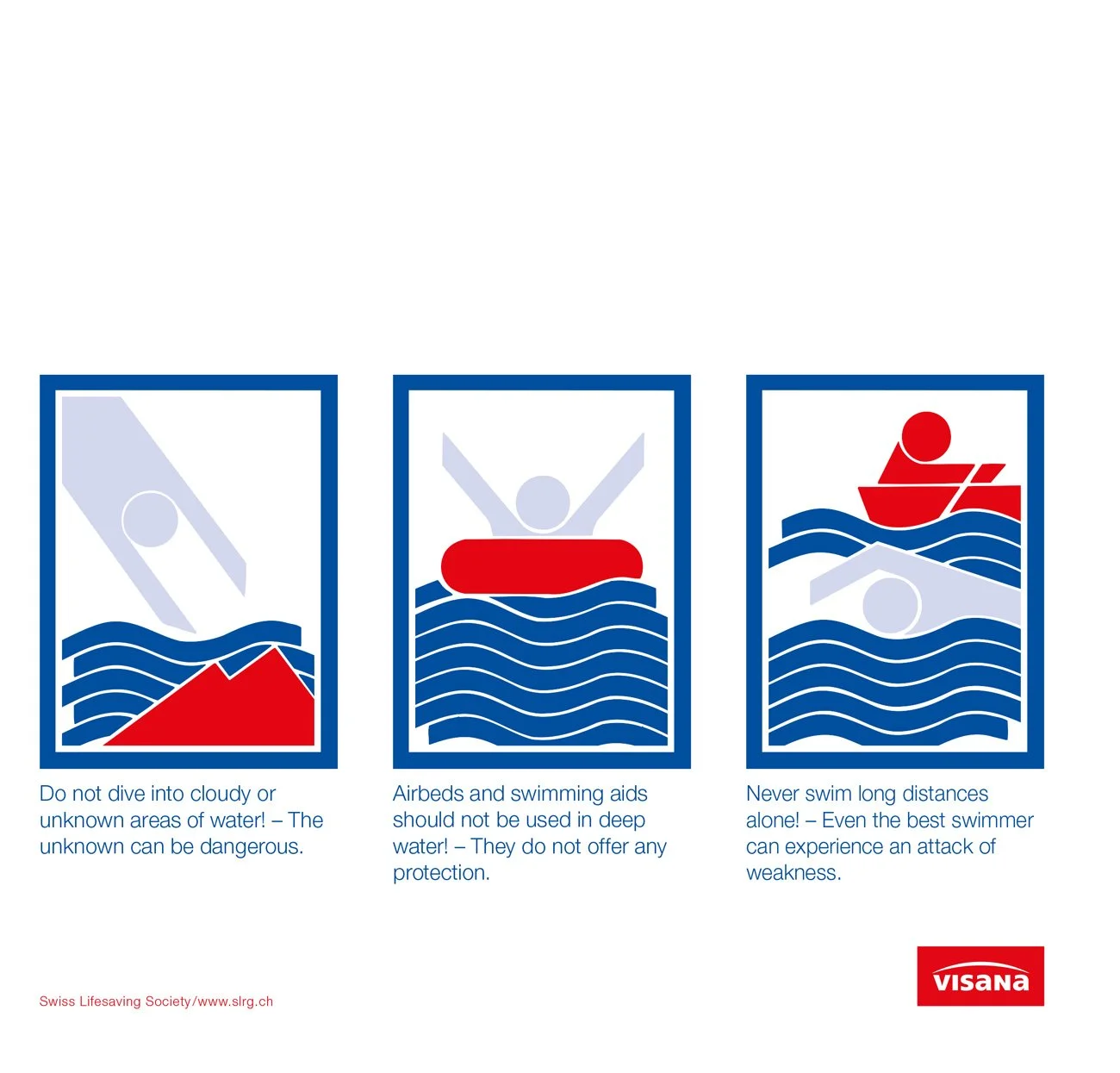

To greatly reduce the risk, swimmers should follow one of the fundamental swimming safety rules: never jump into cold water if you are overheated — always give your body time to adjust. This guidance is part of ▶︎ the basic safety card developed by the Swiss Lifesaving Society. Such simple, well-communicated rules are key: they should be taught from the earliest school years and repeated often at swimming spots. Following them is the best individual protection against accidents and drowning.

Swimmer becomes unconscious after collision, sinks unseen

By following the preventative measures discussed earlier — like cleaning the swimming area of debris — and adhering to basic swimming safety rules, the risk of such severe collisions can be kept very low.

Inexperienced swimmer: swimmer sinks without being spotted because the water is opaque

This risk highlights a wider and deeply important issue: many people, especially children, have not had the chance to learn to swim properly. In Brussels, as in many other places, there is a significant lack of swimming lessons offered at school, which remains a serious public health and safety concern.

Addressing this risk requires both broader swimming education — making sure all children can learn to swim confidently — and individual responsibility. Swimmers must realistically assess their own abilities and those of children or companions. Authorities, in turn, must provide clear, visible information on swimming conditions — including water depth, temperature, possible currents and other relevant factors — both on-site and online. This combination of good education and transparent information empowers individuals to decide responsibly whether they are capable of swimming safely in the canal, thus reducing the likelihood of accidents involving inexperienced swimmers.

Swimmer in distress sinks unseen

Again, the best prevention is following basic safety rules: not swimming alone, swimming with a buddy, and being aware of one’s own limits all help reduce the likelihood of distress.

Swimmer swept away when lock gates open, falls into the lock and cannot be rescued

The places in the southern part of the canal where people currently swim illegally are about 400 metres from the Anderlecht lock. Under normal operation, this lock has little to no effect on the current in the canal. However, during heavy rainstorms the canal acts as a stormwater buffer and can fill quickly. To release this water downstream toward the Scheldt river, weirs next to the lock can be opened, which temporarily creates significant currents. Importantly, this does not happen without warning and typically coincides with bad weather, which in itself deters swimming. The Port of Brussels, as manager of the locks and weirs, could also issue warnings before opening them, which could lead to temporary closure of the swimming area or real-time information at the site and online.

Panic after an incident; location lacks enough exits for many swimmers

A well-designed swimming zone along the southern canal will likely be a long area running parallel to the bank, with a continuous pontoon fitted with numerous ladders or stairs. This design would allow swimmers to leave the water quickly and easily if needed.

Passage of a boat creates suction that can pull swimmers out of the swimming zone and cause collisions

Swimming close to a passing ship can indeed be dangerous, but the actual risk depends on factors like the ship’s size, draught and speed. There are several ways to manage this:

The simplest is to allow swimming only on Sundays, when large commercial ships are not using the canal.

Smaller pleasure boats can be required to slow down when passing the swimming zone, as already happens at other narrow points in the canal when two ships meet.

If swimming is allowed when large ships might pass, the swimming zone could be temporarily narrowed to keep swimmers further from vessels. Ships could be kept away from the swimming area with buoys marking the navigation channel.

For more permanent protection, rigid structures could even be installed in the canal to physically shield the swimming zone.

Swimming in the Rhine in Basel, CH, next to a large cargo ship of 95m length and 11m width. No other safety precautions than good information. There has never been an accidents involving swimmers and vessels, as confirmed by local authorities. Picture © Lucia Mosteyrin.

Health risks: infection via swallowed water or a skin injury

The health risks are mainly related to the sanitary condition of the water and the possibility of infection from bacteria present in it. By law — from local up to European level — swimming water must be tested regularly by a certified laboratory for two specific indicator bacteria: E.coli and Enterococci. These bacteria are not necessarily dangerous themselves, but they indicate possible contamination by other, harder-to-detect germs.

Bacteria levels in the water are volatile and can increase quickly due to factors like heavy rainfall and resulting sewage overflows. That’s why regular testing is so important. According to EU guidelines, water must be tested at the start of the bathing season and then at least once per month. This rather low testing frequency relates to the first risk noted in the Port’s analysis:

The sanitary condition of the water changed between the time of analysis and the time of bathing.

Water quality in places exposed to external factors — like rain washing dirt into the canal or sewage overflows — can change much faster than the legally required testing interval can detect. Additionally, laboratory testing requires an incubation time of 24–48 hours, so results are delayed. However, today there are new ways to track water quality continuously, including automatic tests that deliver immediate results and AI-based prediction models that can forecast expected contamination.

These two innovations — automatic real-time analysis and predictive modelling — are relatively new but have become a game changer for managing water safety.

Automatic testing works through probes in the water that use chemical or biological reactions to detect the presence of E.coli or Enterococci. Results can be transmitted digitally within minutes. These measurements, together with traditional lab tests for verification and historical weather data, are then fed into computer models. Using artificial intelligence, these models learn how weather and water quality relate and can forecast water safety much like a weather forecast. The forecasts are continually refined as new test results come in.

Such systems already operate in several cities. Paris, for example, uses them to ▶︎ monitor water quality at the Seine and the Bassin de la Villette. Copenhagen also uses ▶︎similar tools. Berlin offers ▶︎ a simple website that shows whether water quality meets standards, using a green background for “safe” and red for “not advised”.

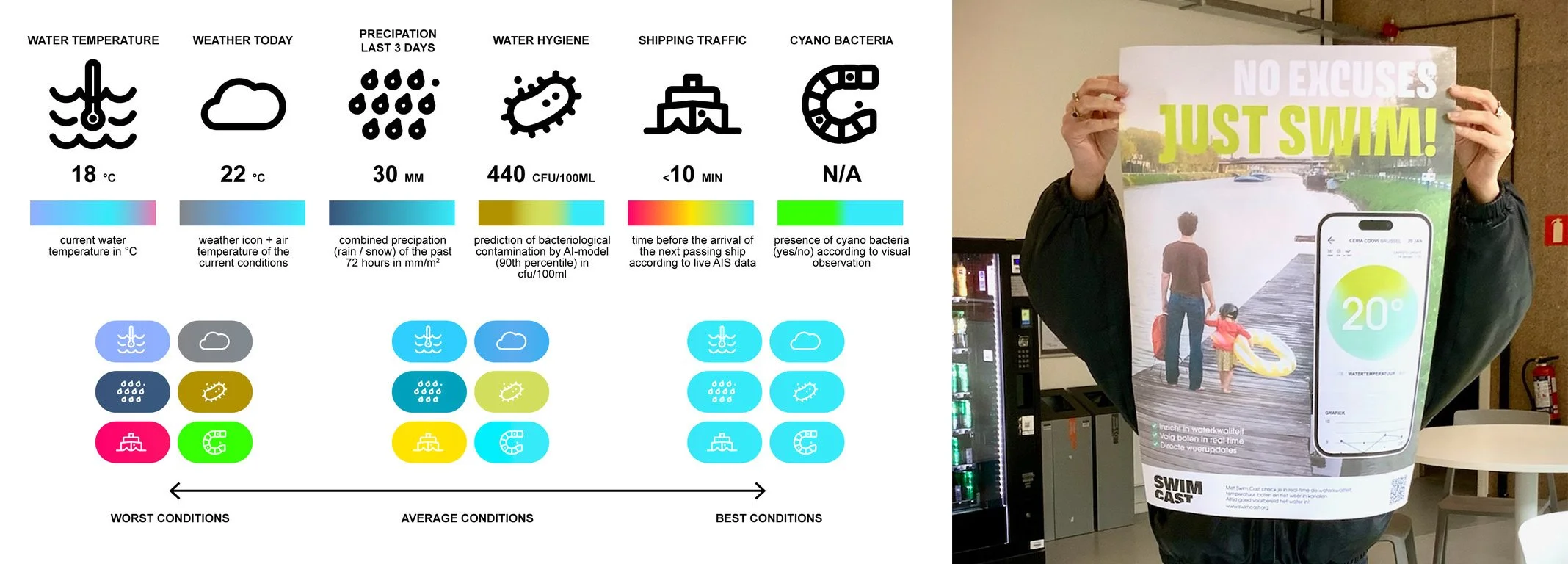

A similar system could easily be installed for the canal in Brussels. It could also be connected to an app or website that bundles together many aspects of swimming safety in one place: recent rainfall, water temperature, bacteria levels, cyanobacteria alerts, and even the real-time approach of large ships. We developed a prototype app called SWIM CAST together with students from the Multimedia and Creative Technology course at Erasmus Brussels University of Applied Sciences and Arts (EhB). The app proved to be a very intuitive way to present this information in a clear summary, while still allowing users to explore more details if they wish.

Parameters and information that could be shared via the future SWIM CAST app. And the beautiful poster made by the students of the EHB.

A germ was not detected during analysis

At first, this might seem like a criticism of the competence of laboratories. More likely, it refers to the risk of infection from germs that are not regularly tested for. As mentioned, E.coli and Enterococci act as indicator bacteria, chosen because detecting them suggests possible presence of other pathogens. This approach is central to the EU bathing water directive. However, it can also be sensible to run additional tests for other germs — for example, Salmonella. As far as we know, Salmonella has never been found in the southern part of the canal, though it has been detected elsewhere in Brussels.

Another potential health risk common in still or slow-moving inland waters is blooms of cyanobacteria, often called blue-green algae. These bacteria can produce toxins like microcystin, which can be harmful to humans and animals. Blooms usually happen under conditions of warm water, high sunlight and high nutrient levels (phosphorus and nitrates) — all of which are common in summer, exactly when people most want to swim.

Fortunately, blooms can often be identified visually, and there are simple tests to check for toxins, which can be verified further in a lab. As far as we know, there has not yet been a bloom in the southern part of the canal. In the future, with enough data, cyanobacteria bloom predictions could also be included in the kind of water safety app described earlier.

Bites or stings from animals or insects

This risk exists everywhere that people swim in natural water, including countless official urban swimming spots worldwide. As noted earlier, animals usually avoid contact with humans. Careful design and management of swimming infrastructure — for example, avoiding waste accumulation that might attract rats — can help keep this risk low.

Presence of heavy metals or other pollutants in the water

Inland waterways sometimes contain remnants of historical pollution: hydrocarbons (oil) or metals from past industry on the banks. Currently, we do not have data on such pollutants in the southern canal, but there has never been heavy industry in this part of the city.

Nevertheless, a comprehensive test for possible chemical pollutants should be carried out to better understand the situation. Unfortunately, there are no regulations for chemical contamination in recreational water. The only guideline comes from the World Health Organization (WHO), which recommends safety thresholds for recreational water roughly 20 times higher than those for drinking water. More information is available in chapter 8 of ▶︎ the WHO report.

The southern part of the canal in 1971 and 2024. Source: bruciel.brussels

Conclusion

We remain convinced that swimming directly in the southern part of the canal could become possible. Right now, it lacks the necessary infrastructure and systems to collect and communicate the information swimmers need to judge conditions — whether provided by an authority or checked by swimmers themselves. However, it would certainly be possible to organise test events to educate the public about the opportunities and challenges, rather than relying on a general ban which is often ignored, leaving swimmers alone without the information needed to make an informed decision.

Swimming carries risks, which differ from pool swimming and therefore need to be addressed differently. But there is no need to exaggerate these risks. Many outdoor swimming spots in similar urban settings show that safe swimming can be managed.

To move forward in Brussels, it will take politicians who recognise the potential and challenges, supporting the idea of swimming in the canal. It will also take a Port authority willing to redefine its role and experiment to make Brussels a more liveable city — using the major asset it controls: the canal.

In a ▶︎ 2022 interview with BRUZZ, the Port of Brussels’ then-new general director said:

“Swimming in the canal, why not? But let’s not forget that the harbour is an economic driver. Swimming on weekdays? I’m not sure that’s feasible. That said, it’s not impossible to go swimming in the canal. Let’s look at it without any taboos.”

Based on this promising statement, we had hoped for more openness to work together on organising the ▶︎ BIG JUMP in 2025. We hope he will hear his own words — and help make swimming in the canal a reality in the near future.

FR

Que diriez-vous d'une baignade dans le canal un dimanche (dans le futur) ?

INTRODUCTION

Il n'existe actuellement aucun site officiel de baignade en plein air à Bruxelles. Néanmoins, les gens continuent de se baigner dans le canal, poussés par la besoin de se rafraîchir et le manque d'alternatives. Cette situation fait involontairement du Port de Bruxelles la seule autorité qui gère dans les faits un site de baignade en plein air dans la ville. La nage dans le canal de Bruxelles pourrait-elle devenir une option reconnue et réaliste pour la baignade en plein air ?

▶︎ Dans un article précédent, nous avons exploré différentes options pour permettre la baignade dans le canal. Cette fois-ci, nous nous concentrons sur l'approche la plus directe et la plus simple : se baigner dans l'eau non traitée du canalde Bruxelles tel qu'il est actuellement. Cette idée soulève naturellement des questions, et à juste titre. Mais nous sommes convaincus qu'avec les mesures adéquates, il est possible d'organiser la baignade dans le canal de manière responsable, sûre et confortable pour tous.

1935, Porte de Ninove : des nageurs dans le canal il y a 90 ans …

… et aujourd'hui, en 2025, au ponton du CRBK à Anderlecht.

Se baigner en milieu urbain est déjà courant dans plusieurs villes, on peut penser à Copenhague, Bâle, et plus récemment Paris et Duisbourg. D'autres villes comme Londres ou Berlin explorent également cette possibilité. Ces villes ont toutes des caractéristiques et des plans d'eau très différents, mais elles partagent une même ambition : devenir des villes où l'on peut se baigner en ouvrant leurs ports, leurs canaux et leurs rivières aux nageurs.

Les avantages de la baignade directement dans le canal de Bruxelles sont évidents : il s'agit du plus grand plan d'eau de la ville, il est suffisamment profond pour la baignade et pourrait être rendu accessible grâce à des infrastructures simples et peu coûteuses, telles que des pontons équipés d'échelles. Le Port de Bruxelles, autorité responsable de la gestion du canal, est ouvert à l'installation de piscines flottantes dans le canal et à la création de zones de baignade séparées de l'eau du canal. Cependant, il reste fermement opposé à la baignade directement dans le canal, même pour des événements occasionnels. Trois raisons à cela : premièrement, la législation interdit purement et simplement la baignade dans le canal ; deuxièmement, leur communication constante sur le danger et l'interdiction de la baignade ; et troisièmement, ce qu'ils considèrent comme des dangers évidents, énumérés dans une analyse des risques qui nous a été communiquée dans le cadre d'une sanction suite à l'événement Big Jump en 2018.

Cet article ambitionne de répondre à cette liste de risques, à les réévaluer et à proposer des méthodes et des techniques pour y remédier, afin que la baignade dans le canal puisse devenir possible de manière sûre et responsable. Mais avant d'examiner les défis spécifiques liés à la gestion des risques de la baignade dans le canal, nous devons examiner comment les risques sont perçus et comment on peut partager la responsabilité pour y faire face.

GÉRER LES RISQUES - CONSIDÉRATIONS GÉNÉRALES

Pour illustrer ce point, prenons l'exemple du risque lié à la baignade, que ce soit dans un canal ou ailleurs, par rapport au risque lié à la circulation routière.

Malgré des règles claires, des infrastructures solides et une éducation du public sur le comportement à adopter dans la circulation, des accidents surviennent, parfois mortels. Pourtant, personne ne proposerait d'interdire aux piétons de marcher dans les rues parce que les voitures existent.

La gestion des risques nécessite une stratégie double. Il incombe à chaque individu d'évaluer ses propres capacités et les circonstances dans lesquelles il se baigne. Pour évaluer cet environnement, les facteurs pertinents doivent être directement visibles ou des informations appropriées doivent être fournies afin que les personnes puissent se forger un avis éclairé. Les autorités ont la responsabilité de créer des infrastructures qui peuvent être reconnues visuellement (par exemple, des plates-formes, des échelles, des escaliers) et de communiquer clairement sur les paramètres que les individus ne peuvent pas évaluer eux-mêmes (ex: qualité de l'eau, courants, température,profondeur). Les autorités doivent également garantir la sécurité en vérifiant et en nettoyant régulièrement le fond de la zone de baignade afin d'enlever les débris ou les déchets. À l'inverse, les individus ont la responsabilité de respecter les règles établies (ex: ne pas jeter de déchets dans l'eau).

Il est toujours possible que des tiers créent un danger, même si tout le monde agit avec prudence. Par exemple, un conducteur peut griller un feu rouge (délibérément ou en raison d'une défaillance technique) et traverser un passage piéton, même si les piétons font confiance au feu vert. La même chose peut se produire sur l'eau : les nageurs peuvent rencontrer des bateaux qui ne respectent pas les règles. Pourtant, la société ne considère pas que traverser la rue au feu vert est particulièrement risqué ; les passages piétons et les feux de signalisation existent partout. Il existe même des passages non signalés, et bien que des accidents se produisent, ils sont rares. Sur l'eau, il y a beaucoup moins de bateaux dans les canaux que de véhicules sur la route. Le risque d'interférence entre les nageurs et les bateaux doit donc être abordé de la même manière, à savoir comme la gestion des risques dans la circulation.

PARTAGE DES RESPONSABILITÉS POUR LA SÉCURITÉ DE LA BAIGNADE EN PLEIN AIR À BRUXELLES - NOTRE VISION

Responsabilités des autorités :

Fournir des infrastructures appropriées

Assurer l'entretien pour garantir la sécurité et la propreté des lieux

Communiquer clairement sur les risques invisibles

Sensibiliser le public aux risques et aux règles de base

Promouvoir les cours de natation

Responsabilités des individus :

S'informer sur les risques et les règles de base

S’informer sur les risques invisibles

Respecter les infrastructures

Évaluer et, si nécessaire, améliorer son niveau de natation

Surveiller les autres (enfants, amis, tiers)

RISQUES LIÉS À LA BAIGNADE EN EAU NATURELL

Comme toute autre activité, la baignade comporte toujours des risques. Dans la circulation, le danger peut être évalué visuellement ; dans le cas de la pollution atmosphérique, il peut parfois être senti ou vu (mais pas toujours). L’eau naturelle, contrairement à une piscine, est opaque et on ne peut complètement la juger avec nos sens. Si la température de l'eau peut être ressentie et évaluée par chacun, la qualité de l'eau (ex: la contamination bactériologique) ne peut être sentie directement. De même, la profondeur ou les objets au fond restent généralement invisibles.

C'est pourquoi quelqu'un doit observer et évaluer ces risques invisibles, et communiquer des informations claires et faciles à comprendre à leur sujet. Cela nécessite une relation de confiance : les individus doivent avoir confiance dans le fait que les autorités fournissent des informations précises et à jour, et les autorités doivent avoir confiance dans le fait que les individus lisent, comprennent et utilisent ces informations de manière responsable.

RISQUES LIÉS À LA BAIGNADE DANS LE CANAL De BRUXELLES

Le Canal de Bruxelles est un plan d'eau artificiel, utilisé aujourd'hui principalement pour la navigation. C'est également le plus grand plan d'eau de la ville. Il sert d'habitat aux poissons et autres espèces aquatiques, agit comme un réservoir d'eau de pluie pendant les tempêtes (ce qui pose des problèmes propres, comme nous le verrons plus loin) et offre un espace ouvert et de larges perspectives dans le paysage urbain dense de Bruxelles. Il est déjà utilisé à des fins récréatives le long de ses quais, parcs et pistes cyclables, ainsi que sur l'eau elle-même, grâce à des clubs d'aviron, kayak, de cours de voile et de croisières en bateau. Mais cela s'arrête là. Le canal pourrait-il également devenir un lieu de baignade ? En réalité, c'est déjà le cas, de manière officieuse. Pour répondre à cette question, nous devons examiner de plus près le canal lui-même et ses risques afférents.

UNE VISION DIFFÉRENCIÉE SUR LE CANAL

Le canal n'est pas comparable à une rivière, qui est généralement un plan d'eau continu et uniforme. Le canal bruxellois est constitué de tronçons d'eau très longs et étroits, reliés uniquement par des écluses, ce qui signifie que les échanges d'eau sont limités dans des conditions normales. À Bruxelles, le canal peut être divisé en trois parties :

La partie sud : de la frontière régionale à Ruisbroek jusqu'à l'écluse d'Anderlecht

La partie centrale : entre les écluses d'Anderlecht et de Molenbeek

La partie nord : de l'écluse de Molenbeek à la frontière régionale avec Vilvorde

Les trois parties du canal à Bruxelles

Déversements d'eaux usées dans la Senne, le canal (points rouges et blancs) et les confluents des cours d'eau dans le canal (points bleus et blancs).

La plupart du temps, l'eau ne s'écoule que lorsque des bateaux passent d'une section plus élevée à une section plus basse. Bien qu'il y ait un écoulement lent et constant du sud vers le nord, il n'y a pratiquement pas de courant dans des conditions normales. Ça peut changer du tout au tout pendant les orages, quand les égouts débordent dans le canal, ce qui crée des courants importants et détériore tout de suite la qualité de l'eau. Ce point est abordé plus en détail ci-dessous. Il est important de noter que ces débordements ne sont pas répartis de manière uniforme : il en existe plusieurs dans le canal central et nord, mais aucun dans la partie sud du territoire bruxellois, et seulement quelques-uns, mineurs, plus au sud, sur le territoire flamand. En conséquence, la qualité de l'eau est en moyenne nettement meilleure dans la partie sud qu'ailleurs.

En Europe, les Etats membres doivent suivre ▶︎ une directive européenne sur l’évaluation de l’eau de baignade. Cette directive définit les règles sur comment attribuer un label de qualité à un endroit de baignade: qualité d’eau excellente, bonne ou suffisante. Cela dit, cette évaluation nécessite des mesures régulières sur une période de 4 ans, avec un certain pourcentage des mesures devant rester en dessous de certains seuils. Il ne définit pas les limites absolues pour un measurement donné. Pour évaluer la qualité d’eau a un moment donné, les autorités locales ont la liberté de définir elles-mêmes les limites. Mais comme il n’existe aucun plan d’eau extérieur baignable à Bruxelles, le gouvernement régional n’a jamais défini ces limites. C’est pourquoi nous avons appliqué ▶︎ le règlement de notre voisin le plus proche: la Flandre.

Sur la base des tests que nous avons effectués à intervals irréguliers les 8 dernières années, nous pouvons affirmer que dans plus de 90 % des analyses, l'eau du canal Sud est propre à la baignade selon les normes appliquées en Flandre pour les zones de baignade en eaux douces intérieures. En revanche, les quelques tests effectués dans les parties centrale et nord n'ont pas permis d’obtenir des résultats qui respectent ces normes. La baignade n'est donc pas recommandée dans ces zones sur la base des données actuelles.

E. coli et entérocoques dans le canal de Bruxelles-Charleroi au CRBK Anderlecht

La morphologie du canal à travers le territoire bruxellois constitue un autre facteur important. Parfois, il n'est large que de 20 mètres, juste assez pour permettre le passage de deux bateaux ; ailleurs, il s'élargit en bassins portuaires pouvant atteindre environ 120 mètres. Sur toute sa longueur, il est principalement bordé de murs de quai pouvant atteindre 5 mètres de haut, mais à certains endroits, on trouve des berges en pente recouvertes de végétation. Certains tronçons sont directement accessibles, tandis que d'autres bordent des sites privés, principalement commerciaux. La profondeur du canal augmente également du sud vers le nord, passant d'environ 3,5 mètres dans les parties sud et centrale à environ 6,5 mètres dans le nord.

Troisièmement, le trafic fluvial varie en fonction des parties du canal. Les grands bateaux ont accès 24 heures sur 24 et 7 jours sur 7 au canal depuis le nord jusqu'au bassin Vergote. C'est également dans la partie nord que se trouvent la plupart des installations commerciales approvisionnées par bateau. Plus au sud, la navigation dépend des heures d'ouverture des écluses, ce qui signifie que le trafic fluvial dans le sud de Bruxelles est en moyenne limité. En outre, la navigation commerciale intérieure est interdite dans toute la Belgique le dimanche. Cela signifie qu'aucune grande péniche ne traverse le centre bruxellois le dimanche et que seuls de petits bateaux de plaisance peuvent circuler.

Ces différences en matière de qualité de l'eau, de morphologie et de trafic fluvial montrent à quel point il est essentiel de distinguer les différentes parties (voire même des points spécifiques) du canal, lorsqu'on examine la possibilité d'y pratiquer la baignade : chaque zone présente des défis et des opportunités à considérer de manière différenciée.

ZOOM SUR LA PARTIE SUD DU CANAL

Compte tenu de tous les facteurs mentionnés ci-dessus, nous pensons que la partie sud du canal est la plus particulièrement adaptée à la baignade pour l'avenir. Dans les sections centrale et nord, pour l'instant, des piscines flottantes ou d'autres installations de baignade utilisant de l'eau séparée du canal lui-même seraient plus appropriées. Dans le sud en revanche, nous voyons une opportunité immédiate pour une baignade directement dans le canal.

Une zone particulièrement intéressante se trouve le long de la rive ouest, entre le club d'aviron et le club de kayak. Entre le ponton du club de kayak et une cale actuellement présente, il y a suffisamment d'espace pour créer une zone de baignade de 50 mètres de long. Des infrastructures simples, telles que des postes de secours et des cabines de change, pourraient être installées sur des pontons flottants. Dans l'eau, une zone de baignade d'environ 50 mètres sur 8 pourrait être aménagée sans gêner le passage des bateaux, des petites embarcations de plaisance ou des amateurs de sports nautiques. Cette zone pourrait être aménagée de manière permanente ou, dans un premier temps, à titre expérimental pendant l'été. Nous pensons que la baignade pourrait même être possible lorsque de grands bateaux passent. Dans tous les cas, un programme de baignade le dimanche pourrait être un bon moyen de tester la baignade dans le canal, vu qu’aucun grand bateau commercial n’y circule le dimanche.

Tout ce qu'il faut, c'est une infrastructure flottante très simple : un ponton, deux rampes d'accès et un cadre léger avec une ligne de bouées pour délimiter une zone de baignade de 50 x 8 m.

PRÊT POUR UNE BAIGNADE LES DIMANCHES ?

COMMENT GÉRER LES RISQUES RELEVÉS PAR LE PORT DE BRUXELLES

Le plus grand défi pour concrétiser cette vision reste de convaincre le Port de Bruxelles, l'autorité qui gère l'ensemble du canal. L'autorisation du Port serait indispensable pour que la baignade soit autorisée. Il est intéressant de noter que la baignade dans cette partie du canal n'est pas totalement interdite par la loi. Le ▶︎ Règlement de police régional applicable au port (en vigueur depuis 2010) ne mentionne pas la baignade. L'autre cadre juridique pertinent est le ▶︎ « Règlement général de police pour la navigation sur les voies navigables intérieures ». L'article 6.37 de ce règlement stipule que la baignade est autorisée si la zone de baignade est correctement signalée par des panneaux de signalisation spécifiques. Cela signifie qu'en principe, la baignade est légalement possible.

Néanmoins, le Port de Bruxelles a réalisé une analyse des risques qui énumère les risques suivants liés à la baignade dans le canal :

Analyse des risques généraux liés à la baignade dans le canal par le Port de Bruxelles, 2018

Risques d'accident – risque de blessures

Coupures ou égratignures dues au contact avec des objets métalliques, du verre ou d'autres objets non détectés au fond ou sur les berges

Plantes épineuses sur les berges

Morsures d'animaux sauvages fréquentant les berges des rivières et des canaux (par exemple, rats)

Blessures lors d'un saut dans l'eau en raison d'un objet contondant non visible au fond

Collision avec un objet flottant juste sous la surface, invisible en raison de l'opacité de l'eau (p. ex. une poutre en bois)

Collision avec un bateau ignorant l'interdiction de naviguer dans la zone de baignade

Risques d'accident – risque de noyade

Hydrocution (choc thermique) : le nageur coule sans être vu en raison de l'opacité de l'eau

Le nageur perd connaissance après une collision et coule sans être vu

Le nageur est inexpérimenté et coule sans être vu

Le nageur est en détresse et coule sans être vu

Le nageur est emporté par le courant suite à l’ouverture du barrage d’écluse, tombe dans le barrage avant d’avoir pu être sauvé

Panique après un incident ; le site ne dispose pas de suffisamment de sorties pour permettre à de nombreux nageurs de quitter rapidement l'eau

Le passage d'un bateau crée un effet de succion qui pourrait tirer des nageurs hors de la zone de baignade, entraînant des collisions dangereuses

Risques pour la santé

Les conditions sanitaires de l'eau changent entre le moment du prélèvement et celui de la baignade

Un germe nocif non détecté lors des tests

Morsures ou piqûres d'animaux (par exemple, rats) ou d'insectes

Présence de métaux lourds ou d'autres polluants dans l'eau

Il est important de souligner que ces risques ne sont pas propres au canal bruxellois ; ils s'appliquent également à pratiquement tous les sites de baignade naturels. En effet, la baignade est pratiquée dans de nombreux autres sites présentant des conditions similaires, tant en Belgique (par exemple, de manière saisonnière au Keerdok à Malines, au Bonapartedok à Anvers et dans les canaux de Bruges, ou lors d'événements dans le port de Gand et aux ▶︎ différents endroits où le BIG JUMP peut avoir lieu en Belgique) qu'à l'étranger.

RISQUES D'ACCIDENT – RISQUES DE BLESSURES

Coupures, égratignures ou fractures causées par le contact avec un objet métallique, du verre ou d'autres débris non détectés au fond ou sur la rive

Il s'agit en effet d'un risque réel, et des cas de personnes ayant touché ou s'étant blessées sur des objets submergés ont été signalés. Par le passé, des vélos ont été retirés du canal près du ponton du CRBK. Afin de rendre la baignade plus sûre, le fond du canal dans la zone où les personnes pourraient plonger devrait être nettoyé par des plongeurs afin d'enlever les débris. Nous avons collaboré avec une société de plongée locale pour effectuer ce travail lors de ▶︎ l'Expedition Swim en 2019. Ailleurs, comme en Flandre, ce travail est souvent effectué par des plongeurs des pompiers. Le nettoyage devrait être effectué avant la principale saison de baignade en été et peut être répété en milieu de saison si nécessaire. En outre, l'organisation qui gère la zone de baignade peut effectuer régulièrement des inspections du fond en traînant des filets pour détecter tout nouveau débris. Si des débris sont trouvés, des plongeurs peuvent alors être appelés pour les retirer. Des panneaux sur le ponton doivent informer les personnes de la profondeur de l'eau et la baignade peut être déconseillée si l'eau est trop peu profonde. Ces mesures permettent de réduire considérablement le risque de blessures.

Plantes épineuses sur les berges

Les plantes qui poussent le long des berges doivent simplement être coupées à tous les endroits où les baigneurs pourraient entrer en contact avec elles. Cette tâche incombe à l'organisation responsable de l'entretien de la zone de baignade.

Morsures d'animaux sauvages fréquentant les berges des rivières et des canaux (par exemple, les rats)

En général, les animaux, y compris les rats, ont tendance à avoir plus peur des humains que l'inverse. Les morsures entraînant des blessures ou des infections sont rares, mais elles peuvent arriver. Pour réduire encore ce risque, des pontons pourraient être placés à une certaine distance (environ un mètre) de la rive. Un nettoyage régulier et l'élimination rapide de tous les déchets susceptibles d'attirer les rats contribueront à rendre la zone de baignade moins attrayante pour ces animaux, réduisant ainsi les risques de rencontre.

Blessures lors d'un plongeon dans l'eau en raison d'objets contondants invisibles

Les mêmes mesures préventives mentionnées précédemment (inspections régulières des plongeoirs, nettoyage et balayage du fond à l'aide d'un filet) s'appliquent ici également.

Collision avec un objet flottant juste sous la surface, invisible en raison de l'opacité de l'eau

Une solution pratique consiste à délimiter la zone de baignade à l'aide d'une ligne de bouées auxquelles est fixé un filet descendant jusqu'au fond. Ce filet empêchera les objets de flotter dans la zone de baignade. Il convient également de noter que dans la partie sud du canal, il y a généralement moins de débris flottants que dans les autres sections.

Collision avec un bateau qui ignore l'interdiction de naviguer dans la zone de baignade

Ce risque peut résulter d'une erreur humaine ou de problèmes techniques. La mesure la plus importante consiste à informer clairement tous les conducteurs de bateaux et de navires de l'emplacement de la zone de baignade. Pour ce faire, il convient de placer les panneaux de signalisation requis bien avant la zone et de marquer clairement la zone de baignade elle-même à l'aide de bouées et de lignes flottantes bien visibles. Pour les zones de baignade permanentes, des structures de protection supplémentaires telles que des poteaux ou des poutres déflectrices peuvent également être installées dans le canal, mais cette option est plus coûteuse.

Outre les mesures visant les bateaux, les nageurs eux-mêmes peuvent également être alertés de l'approche de navires. Cela peut être fait par des sauveteurs ou du personnel chargé de la gestion de la zone de baignade qui surveillent visuellement, ou par l'installation de systèmes de caméras surveillant le canal dans les deux sens. Ces caméras peuvent être reliées à un logiciel de reconnaissance d'images qui détecte automatiquement les bateaux qui approchent et déclenche un avertissement sonore ou visuel dans la zone de baignade, permettant ainsi aux baigneurs de sortir de l'eau à temps et en toute sécurité.

Si la baignade est autorisée à des moments où de grands navires commerciaux peuvent passer, les baigneurs pourraient également être avertis en temps réel grâce aux données du ▶︎ système d'identification automatique (AIS) des navires. Ce système transmet la position, la route et la vitesse de chaque navire au moins toutes les 30 secondes. Si un nombre suffisant de récepteurs AIS est installé le long du canal, il est possible de prédire très précisément la trajectoire d'un navire. Ces données sont déjà visualisées sur des sites web tels que ▶︎ MarineTraffic et ▶︎ VesselFinder. Les données AIS pourraient être intégrées dans un système local afin de déclencher des avertissements ou des alertes sur place dans une application dédiée à la baignade.

RISQUES D'ACCIDENT – RISQUE DE NOYADE

Les points soulevés concernant la noyade ne portent pas tant sur le risque de noyade en soi que sur le fait qu'une personne en train de se noyer pourrait ne pas être visible par les sauveteurs ou les autres nageurs en raison de l'opacité de l'eau du canal. Dans la partie sud du canal, la clarté de l'eau, ou profondeur visible, est d'environ 60 cm.

Ce niveau d'opacité est très courant pour les eaux de baignade naturelles en Europe centrale. D'innombrables zones de baignade, dont beaucoup en Belgique, ont des eaux tout aussi opaques, mais les gens s'y baignent en toute sécurité chaque année. Le fait que ces lieux soient autorisés et correctement équipés montre que le risque n'est pas inacceptable, mais qu'il peut être géré.

Il est également important de noter que les sauveteurs repèrent généralement les nageurs en difficulté non pas en les voyant sous l'eau, mais en observant leur comportement à la surface. La plupart des sauvetages commencent parce que quelqu'un remarque des signes de détresse au-dessus de l'eau. Une transparence totale de l'eau peut aider, mais elle n'est pas strictement indispensable si la surveillance est effectuée correctement.

Hydrocution : le nageur coule sans être vu parce que l'eau est opaque

L'hydrocution, également connue sous le nom de choc thermique, peut se produire lorsqu'une personne en état d'hyperthermie due à l'exposition au soleil ou à l'exercice physique entre soudainement dans l'eau froide, ce qui entraîne un changement rapide de température. Cela peut déclencher des réactions dangereuses telles qu'un évanouissement ou même un arrêt cardiaque, pouvant entraîner la noyade.

Pour réduire considérablement ce risque, les nageurs doivent respecter l'une des règles fondamentales de sécurité aquatique : ne jamais plonger dans l'eau froide si vous avez trop chaud, mais toujours laisser à votre corps le temps de s'adapter. Cette recommandation fait partie de ▶︎ la fiche de sécurité de base élaborée par la Société Suisse de Sauvetage. Des règles simples et bien communiquées sont essentielles : elles doivent être enseignées dès les premières années d'école et répétées régulièrement sur les lieux de baignade. Leur respect constitue la meilleure protection individuelle contre les accidents et la noyade.

Un nageur devient inconscient après une collision et coule sans être vu.

En suivant les mesures préventives évoquées précédemment, telles que le nettoyage de la zone de baignade, et en respectant les règles élémentaires de sécurité aquatique, le risque de collisions graves peut être réduit au minimum.

Nageur inexpérimenté : le nageur coule sans être vu car l'eau est opaque.

Ce risque met en évidence un problème plus large et extrêmement important : de nombreuses personnes, en particulier les enfants, n'ont pas eu la chance d'apprendre à nager correctement. À Bruxelles, comme dans de nombreux autres endroits, l'enseignement de la natation à l'école est largement insuffisant, ce qui reste un grave problème de santé et de sécurité publique.

Pour remédier à ce risque, il faut à la fois élargir l'enseignement de la natation, en veillant à ce que tous les enfants puissent apprendre à nager en toute confiance, et responsabiliser les individus. Les nageurs doivent évaluer de manière réaliste leurs propres capacités et celles des enfants ou de leurs compagnons. Les autorités, quant à elles, doivent fournir des informations claires et visibles sur les conditions de baignade, notamment la profondeur de l'eau, la température, les courants éventuels et d'autres facteurs pertinents, tant sur place qu'en ligne. Cette combinaison d'une bonne éducation et d'informations transparentes permet à chacun de décider de manière responsable s'il est capable de nager en toute sécurité dans le canal, réduisant ainsi le risque d'accidents impliquant des nageurs inexpérimentés.

Un nageur en détresse coule sans être vu.

Encore une fois, la meilleure prévention consiste à respecter les règles de sécurité élémentaires : ne pas nager seul, nager avec un partenaire et connaître ses propres limites contribuent à réduire les risques de détresse.

Nageur emporté par le courant suite à l’ouverture du barrage d’écluse, tombe dans le barrage avant d’avoir pu être sauvé.

Les endroits où des personnes se baignent actuellement illégalement dans la partie sud du canal se trouvent à environ 400 mètres de l'écluse d'Anderlecht. En situation normale, ce cadenas n'a que peu ou pas d'effet sur le courant dans le canal. Cependant, lors de fortes pluies, le canal sert de réservoir d'eaux pluviales et peut se remplir rapidement. Pour évacuer cette eau vers l'Escaut, des vannes situées à côté du cadenas peuvent être ouvertes, ce qui crée temporairement des courants importants. Il est important de noter que cela ne se produit pas sans avertissement et coïncide généralement avec du mauvais temps, ce qui dissuade en soi de se baigner. Le Port de Bruxelles, en tant que gestionnaire des écluses et des déversoirs, pourrait également émettre des avertissements avant leur ouverture, ce qui pourrait entraîner la fermeture temporaire de la zone de baignade ou la diffusion d'informations en temps réel sur place et en ligne.

Panique après un incident ; le site ne dispose pas de suffisamment de sorties pour les nombreux baigneurs.

Une zone de baignade bien conçue le long du canal sud serait probablement une longue zone parallèle à la rive, avec un ponton continu équipé de nombreuses échelles ou escaliers. Cette conception permettrait aux baigneurs de sortir rapidement et facilement de l'eau en cas de besoin.

Le passage d'un bateau crée un effet de succion qui peut entraîner les baigneurs hors de la zone de baignade et provoquer des collisions.

La baignade à proximité d'un bateau en passage peut en effet être dangereuse, mais le risque réel dépend de facteurs tels que la taille, le tirant d'eau et la vitesse du bateau. Il existe plusieurs moyens de gérer cela :

le plus simple est d'autoriser la baignade uniquement le dimanche, lorsque les grands navires commerciaux n'utilisent pas le canal.

Les bateaux de plaisance plus petits peuvent être tenus de ralentir lorsqu'ils passent dans la zone de baignade, comme c'est déjà le cas à d'autres endroits étroits du canal lorsque deux bateaux se croisent.

Si la baignade est autorisée lorsque de grands bateaux peuvent passer, la zone de baignade pourrait être temporairement rétrécie afin d'éloigner les baigneurs des bateaux. Les bateaux pourraient être tenus à l'écart de la zone de baignade à l'aide de bouées balisant le chenal de navigation.

Pour une protection plus permanente, des structures rigides pourraient même être installées dans le canal afin de protéger physiquement la zone de baignade.

Baignade dans le Rhin à Bâle, en Suisse, à proximité d'un grand bateau de transport de 95 mètres de long et 11 mètres de large. Aucune mesure de sécurité n'est prise, hormis des informations claires. Aucun accident impliquant des nageurs et des bateaux n'a jamais été signalé, comme le confirment les autorités locales. Photo © Lucia Mosteyrin.

RISQUES POUR LA SANTÉ : INFECTION PAR INGESTION D'EAU OU PAR UNE BLESSURE DE LA PEAU

Les risques pour la santé sont principalement liés à l'état sanitaire de l'eau et à la possibilité d'infection par des bactéries présentes dans celle-ci. Conformément à la législation, tant au niveau local qu'européen, l'eau de baignade doit être régulièrement analysée par un laboratoire agréé afin de détecter la présence de deux bactéries indicatrices spécifiques : E. coli et Enterococci. Ces bactéries ne sont pas nécessairement dangereuses en elles-mêmes, mais elles indiquent une possible contamination par d'autres germes plus difficiles à détecter.

Les niveaux de bactéries dans l'eau sont instables et peuvent augmenter rapidement en raison de facteurs tels que de fortes précipitations et les débordements d'égouts qui en résultent. C'est pourquoi il est si important de procéder à des analyses régulières. Selon les directives de l'UE, l'eau doit être analysée au début de la saison balnéaire, puis au moins une fois par mois. Cette fréquence d'analyse plutôt faible est liée au premier risque relevé dans l'analyse du Port :

Les conditions sanitaires de l'eau ont changé entre le moment de l'analyse et le moment de la baignade.

La qualité de l'eau dans les endroits exposés à des facteurs externes, tels la pluie qui entraîne des saletés dans le canal ou les débordements d'égouts, peut changer beaucoup plus rapidement que ne le permet l'intervalle de contrôle légalement requis. De plus, les tests en laboratoire nécessitent un temps d'incubation de 24 à 48 heures, ce qui retarde les résultats. Cependant, il existe aujourd'hui de nouveaux moyens de surveiller la qualité de l'eau en continu, notamment des tests automatiques qui fournissent des résultats immédiats et des modèles de prévision basés sur l'IA qui peuvent prévoir la contamination attendue.

Ces deux innovations — l'analyse automatique en temps réel et la modélisation prédictive — sont relativement récentes, mais elles ont révolutionné la gestion de la sécurité de l'eau.

Les tests automatiques fonctionnent à l'aide de sondes placées dans l'eau qui utilisent des réactions chimiques ou biologiques pour détecter la présence d'E. coli ou d'entérocoques. Les résultats peuvent être transmis numériquement en quelques minutes. Ces mesures, associées à des tests de laboratoire traditionnels à fin de vérification et à des données météorologiques historiques, sont ensuite intégrées à des modèles informatiques. Grâce à l'intelligence artificielle, ces modèles apprennent comment la météo et la qualité de l'eau sont liées et peuvent prédire le niveau de sécurité de l'eau, un peu comme une prévision météorologique. Les prévisions sont continuellement affinées à mesure que de nouveaux résultats de tests sont disponibles.

De tels systèmes sont déjà en place dans plusieurs villes. Paris, par exemple, les utilise pour ▶︎ surveiller la qualité de l'eau de la Seine et du Bassin de la Villette. Copenhague utilise également ▶︎ des outils similaires. Berlin propose ▶︎ un site web simple qui indique si la qualité de l'eau est conforme aux normes, en utilisant un fond vert pour « sûr » et rouge pour « déconseillé ».

Un système similaire pourrait facilement être installé pour le Canal de Bruxelles. Il pourrait également être relié à une application ou à un site web regroupant de nombreux pans de sécurité de la baignade en un seul endroit : précipitations récentes, température de l'eau, niveaux de bactéries, alertes cyanobactéries et même approche en temps réel des grands navires. Nous avons développé un prototype d'application appelé SWIM CAST en collaboration avec des étudiants du cours « Multimédia et technologies créatives » de l'Erasmus Brussels University of Applied Sciences and Arts (EhB). L'application s'est avérée être un moyen très intuitif de présenter ces informations sous forme de résumé clair, tout en permettant aux utilisateurs d'explorer plus en détail s'ils le souhaitent.

Paramètres et informations pouvant être partagés via la future application SWIM CAST. Et la magnifique affiche réalisée par les étudiants de l'EHB.

Un certain agent pathogène n'a pas été détecté lors de l'analyse

À première vue, cela pourrait sembler critiquer la compétence des laboratoires. Il s'agit plus probablement du risque d'infection par des agents pathogènes qui ne font pas l'objet de tests réguliers. Comme mentionné précédemment, E. coli et les entérocoques sont des bactéries indicatrices, choisies parce que leur détection suggère la présence possible d'autres agents pathogènes. Cette approche est au cœur de la directive européenne sur les eaux de baignade. Cependant, il peut également être judicieux d'effectuer des tests supplémentaires pour d'autres germes, par exemple la salmonelle. À notre connaissance, la salmonelle n'a jamais été détectée dans la partie sud du canal, bien qu'elle ait été détectée ailleurs dans la région bruxelloise.

Un autre risque sanitaire potentiel courant dans les eaux intérieures stagnantes ou à faible débit est la prolifération de cyanobactéries, souvent appelées algues bleues. Ces bactéries peuvent produire des toxines telles que la microcystine, qui peut être nocive pour les humains et les animaux. La prolifération se produit généralement dans des conditions d'eau chaude, de fort ensoleillement et de niveaux élevés de nutriments (phosphore et nitrates), toutes ces conditions étant courantes en été, précisément lorsque les gens souhaitent le plus se baigner.

Heureusement, les proliférations sont souvent visibles à l'œil nu et il existe des tests simples pour détecter les toxines, qui peuvent être vérifiées en laboratoire. À notre connaissance, aucune prolifération n'a encore été observée dans la partie sud du canal. À l'avenir, si l'on dispose de données suffisantes, les prévisions de prolifération de cyanobactéries pourraient également être intégrées dans le type d'application de sécurité aquatique décrit précédemment.

Morsures ou piqûres d'animaux ou d'insectes

Ce risque existe partout où les gens se baignent dans des eaux naturelles, y compris dans d'innombrables lieux de baignade officiels en milieu urbain à travers le monde. Comme indiqué précédemment, les animaux évitent généralement tout contact avec les humains. Une conception et une gestion rigoureuses des infrastructures de baignade, par exemple en évitant l'accumulation de déchets susceptibles d'attirer les rats, peuvent contribuer à réduire ce risque.

Présence de métaux lourds ou d'autres polluants dans l'eau

Les voies navigables intérieures contiennent parfois des traces de pollution historique : hydrocarbures (pétrole) ou métaux provenant d'anciennes industries installées sur les berges. À l'heure actuelle, nous ne disposons pas de données sur ces polluants dans le canal Sud, mais il n'y a jamais eu d'industrie lourde dans cette partie de la ville.

Néanmoins, un test complet visant à détecter d'éventuels polluants chimiques devrait être effectué afin de mieux comprendre la situation. Malheureusement, il n'existe aucune réglementation en matière de contamination chimique des eaux récréatives. La seule directive provient de l'Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS), qui recommande des seuils de sécurité pour les eaux récréatives environ 20 fois plus élevés que ceux fixés pour l'eau potable. De plus amples informations sont disponibles au chapitre 8 du ▶︎ rapport de l'OMS.

La partie sud du canal en 1971 et en 2024. Source : bruciel.brussels

CONCLUSION

Nous restons convaincus que la baignade dans la partie sud du canal peut devenir possible. À l'heure actuelle, il manque les infrastructures et les systèmes nécessaires pour collecter et communiquer les informations dont les baigneurs ont besoin pour évaluer les conditions, qu'elles soient fournies par une autorité ou vérifiées par les baigneurs eux-mêmes. Toutefois, il est clairement possible d'organiser des événements test afin d'informer le public des opportunités et des défis, plutôt que de s'appuyer sur une interdiction générale qui est souvent ignorée, laissant les baigneurs sans les informations nécessaires pour prendre une décision éclairée.

La baignade comporte des risques, qui diffèrent de ceux de la natation en piscine et doivent donc être abordés différemment. Cependant, il n'est pas nécessaire d'exagérer ces risques. De nombreux sites de baignade en plein air dans des environnements urbains similaires montrent qu'il est possible de garantir la sécurité des baigneurs.

Pour aller de l'avant à Bruxelles, il faudra que les responsables politiques reconnaissent le potentiel et les défis, et soutiennent l'idée de la baignade dans le canal. Il faudra également que l'autorité portuaire soit disposée à redéfinir son rôle et à expérimenter pour rendre Bruxelles plus vivable, en utilisant l'atout majeur dont elle dispose : le canal.

Dans une ▶︎ interview accordée en 2022 à BRUZZ, le nouveau directeur général du Port de Bruxelles déclarait :

“Se baigner dans le canal, pourquoi pas ? Mais n’oublions pas que le port est un moteur économique. Se baigner en semaine ? Je ne suis pas sûr que ce soit faisable. Cela dit, il n’est pas impossible de se baigner dans le canal. Examinons la question sans tabous.”

Sur la base de cette déclaration prometteuse, nous espérions une plus grande ouverture pour collaborer à l'organisation du ▶︎ BIG JUMP en 2025. Nous espérons qu'il se souviendra de ses propres paroles et qu'il contribuera à faire de la baignade dans le canal une réalité dans un avenir proche.

NL

Wat als we zondag’s in het kanaal kunnen zwemmen (in toekomst)?

INLEIDING

Vandaag de dag is er geen officiële openluchtzwemlocatie meer in Brussel. Toch zwemmen er nog steeds mensen in het kanaal - uit noodzaak en bij gebrek aan alternatieven. Door deze situatie is de Haven van Brussel onbedoeld de enige instantie die effectief een buitenzwemplek in de stad beheert. Zou zwemmen in het kanaal in Brussel een volwaardige, officiële optie voor openluchtzwemmen kunnen worden?

▶︎ In een vorig artikel hebben we verschillende opties onderzocht om zwemmen in het kanaal mogelijk te maken. Deze keer richten we ons op de meest directe en eenvoudige aanpak: zwemmen in het bestaande, onbehandelde water van het Brusselse kanaal zelf. Het is begrijpelijk dat dit idee vragen oproept, en terecht. Maar we zijn ervan overtuigd dat het met de juiste maatregelen mogelijk is om zwemmen in het kanaal op een verantwoorde, veilige en comfortabele manier voor iedereen te organiseren.

1935 aan de Ninoofse Poort: kanaalzwemmers 90 jaar geleden …

... en vandaag in 2025 aan de steiger van de CRBK in Anderlecht.

Zwemmen in de stad is al heel gewoon in een paar steden, zoals Kopenhagen, Bazel, en sinds kort ook Parijs en Duisburg. Andere steden, zoals Londen en Berlijn, kijken ook naar wat er mogelijk is. Al deze steden zijn heel verschillend en hebben andere wateren, maar ze willen allemaal hetzelfde: een stad waar je kunt zwemmen door havens, kanalen en rivieren toegankelijk te maken.

De voordelen van zwemmen in het kanaal in Brussel zijn duidelijk: het is het grootste water in de stad, diep genoeg om te zwemmen en het kan makkelijk toegankelijk worden gemaakt met simpele, goedkope voorzieningen zoals steigers met ladders. Maar hoewel de Haven van Brussel – de verantwoordelijke overheid voor het kanaal – openstaat voor drijvende zwembaden in het kanaal en zwemzones die zijn afgescheiden van het kanaalwater, blijft ze er stellig tegen dat er in het kanaal zelf wordt gezwommen, zelfs niet voor occasionele evenementen. Daar zijn drie redenen voor: ten eerste is zwemmen in het kanaal gewoon verboden door de wet; ten tweede zeggen ze steeds dat zwemmen gevaarlijk is en daarom niet mag; en ten derde zien ze duidelijke gevaren, die ze hebben opgeschreven in een risicoanalyse die ze ons hebben gegeven als deel van een boete na het Big Jump-evenement in 2018.

Dit artikel wil op die lijst van risico's ingaan, ze re-evalueren en methoden en technieken voorstellen om ze aan te pakken, zodat zwemmen in het kanaal op een veilige en verantwoorde manier mogelijk wordt. Maar voordat we kijken naar de specifieke uitdagingen van het beheer van de risico's van openluchtzwemmen in het kanaal, moeten we eerst eens kijken hoe risico's worden ervaren en hoe de verantwoordelijkheid voor het aanpakken ervan kan worden gedeeld.

Omgaan met risico's in het algemeen

Risico's moeten realistisch worden ingeschat. Ze kunnen wel zo goed mogelijk worden beheerd, maar nooit helemaal worden geëlimineerd.

Om dit te verduidelijken, kun je het risico van zwemmen – in een kanaal of ergens anders – vergelijken met het risico van verkeer. Ongelukken gebeuren, soms met dodelijke afloop, ondanks duidelijke regels, een goede infrastructuur en voorlichting over hoe je je in het verkeer moet gedragen. Toch zou niemand voorstellen om voetgangers te verbieden op straat te lopen omdat er auto's bestaan.

Risico's beheren vereist een tweeledige strategie. Het is de verantwoordelijkheid van ieder individu om zijn eigen capaciteiten en de omstandigheden om hem heen in te schatten. Om die omstandigheden te kunnen beoordelen, moeten de relevante factoren direct zichtbaar zijn of moet er goede informatie worden verstrekt, zodat mensen een weloverwogen oordeel kunnen vellen. Overheden moeten zorgen voor infrastructuur die je kunt beoordelen (zoals platforms, ladders, trappen) en duidelijk informatie geven over dingen die je niet zelf kunt inschatten (zoals waterkwaliteit, stroming, temperatuur, diepte). Ook moeten ze de veiligheid garanderen door bijvoorbeeld de bodem van de zwemzone regelmatig te controleren en schoon te maken om troep te verwijderen. Omgekeerd hebben individuen de verantwoordelijkheid om de algemene regels te volgen, zoals geen afval in het water gooien.

Het is altijd mogelijk dat derden gevaar veroorzaken, ook al gedraagt iedereen zich voorzichtig. Een automobilist kan bijvoorbeeld door het rode licht rijden (opzettelijk of door een technische storing) door een oversteekplaats, ook al vertrouwden de voetgangers op het groene licht. Hetzelfde kan op het water gebeuren: zwemmers kunnen boten tegenkomen die zich niet aan de regels houden. Toch ziet de samenleving het oversteken van de straat bij groen licht niet als bijzonder riskant; zebrapaden en verkeerslichten zijn overal aanwezig. Er zijn zelfs ongemarkeerde oversteekplaatsen, en hoewel er wel eens ongelukken gebeuren, zijn deze zeldzaam. Op het water zijn er veel minder boten in het kanaal dan voertuigen op de weg. Het risico dat zwemmers en boten elkaar hinderen, moet daarom op dezelfde manier worden benaderd als het beheersen van risico's in het verkeer.